Monday, February 19, 2007

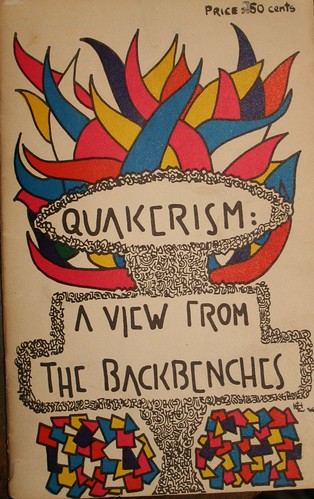

Quakerism: a view from the back benches

Quakerism: a view from the back benches

Copyright 1966 The Back Benches

INTRODUCTION

TO FRIENDS WITH LOVE

More than a year ago the writers of this pamphlet came together to explore our feelings about the Society of Friends. Though we came from different Meetings - and of a widely differing character - for each of us the Society had been a religious home. Not one of us felt he could find as real a home in another fellowship, yet each of us in his own way had been deeply troubled by the condition of the Society today: its divisions, its confusions, its lack of witness and lack of light for the future. That others share this feeling is shown by the articles on religious renewal which appear often in Friends’ publications and by the emergence of groups seeking spiritual clarity and new purpose for the Society - all symptoms of striving and desire for change.

We started our discussions in a pervasive attitude of frustration and near-despair, a sort of “last- chance” atmosphere. Each of us shared a dilemma: involvement and yet dissatisfaction with our Meeting. We asked the questions: What are we called to do with our time, energies, and talents- limited as they are? Can new life grow within our Meetings? Can they become instruments of new life in the world?

As almost anyone could have told us, we have not found the answers to the questions we posed. These essays are the fruit of our sessions of searching, our doubts and affirmations. We hope that our writings show that we care for the Society of Friends and that they reflect the means which Quakerism has had for us. They are meant as a spur for debate; they are unfinished papers for each person to complete in his own way.

Though our discussions encompassed the Society in all its aspects, which really cannot be neatly separated and categorized for formal reasons we have written separate critiques of the Meeting as a community; Friends’ testimonies; worship; Friends’ form of organization, the meeting for business, and our attitudes toward conflict and controversy within the Meeting.

We have met five times as a group, each time becoming more aware of each other as individuals and of our differences. Through laboring together on this job, we have caught a glimpse of the answer to a question we didn’t come together to ask: how does a real feeling of unity arise? It is by working together on something of real importance to us, drawing upon intellect, emotion, patience, humor and worship. We have experienced part of the fruits of our labor in the very act of meeting together: a feeling of what is meant by the “blessed community” which is invisible and geographically dispersed, but nevertheless real.

For all Friends who find there life in the Society of Friends less than complete and fulfilling, we recommend this kind of group searching. While it may not yield the “new life” we seek, it may at least prepare the earth and plant some seeds so that new life may grow.

With special thanks for the help of Berit Lakey, and with appreciation to Jan Rachel, Sarah, Leslie, and Heikki Arvio, Christopher and Beth Flanagan, Christiana Lakey and Mark, Scott, Lynn and Melissa Taylor.

Copyright 1966 The Back Benches

INTRODUCTION

TO FRIENDS WITH LOVE

More than a year ago the writers of this pamphlet came together to explore our feelings about the Society of Friends. Though we came from different Meetings - and of a widely differing character - for each of us the Society had been a religious home. Not one of us felt he could find as real a home in another fellowship, yet each of us in his own way had been deeply troubled by the condition of the Society today: its divisions, its confusions, its lack of witness and lack of light for the future. That others share this feeling is shown by the articles on religious renewal which appear often in Friends’ publications and by the emergence of groups seeking spiritual clarity and new purpose for the Society - all symptoms of striving and desire for change.

We started our discussions in a pervasive attitude of frustration and near-despair, a sort of “last- chance” atmosphere. Each of us shared a dilemma: involvement and yet dissatisfaction with our Meeting. We asked the questions: What are we called to do with our time, energies, and talents- limited as they are? Can new life grow within our Meetings? Can they become instruments of new life in the world?

As almost anyone could have told us, we have not found the answers to the questions we posed. These essays are the fruit of our sessions of searching, our doubts and affirmations. We hope that our writings show that we care for the Society of Friends and that they reflect the means which Quakerism has had for us. They are meant as a spur for debate; they are unfinished papers for each person to complete in his own way.

Though our discussions encompassed the Society in all its aspects, which really cannot be neatly separated and categorized for formal reasons we have written separate critiques of the Meeting as a community; Friends’ testimonies; worship; Friends’ form of organization, the meeting for business, and our attitudes toward conflict and controversy within the Meeting.

We have met five times as a group, each time becoming more aware of each other as individuals and of our differences. Through laboring together on this job, we have caught a glimpse of the answer to a question we didn’t come together to ask: how does a real feeling of unity arise? It is by working together on something of real importance to us, drawing upon intellect, emotion, patience, humor and worship. We have experienced part of the fruits of our labor in the very act of meeting together: a feeling of what is meant by the “blessed community” which is invisible and geographically dispersed, but nevertheless real.

For all Friends who find there life in the Society of Friends less than complete and fulfilling, we recommend this kind of group searching. While it may not yield the “new life” we seek, it may at least prepare the earth and plant some seeds so that new life may grow.

Cynthia Arvio

Raymond Paavo Arvio

Fred Bunker Davis

Dorothy Flanagan

Ross Flanagan

George Lakey

Vonna Taylor

William Taylor

June 1966

With special thanks for the help of Berit Lakey, and with appreciation to Jan Rachel, Sarah, Leslie, and Heikki Arvio, Christopher and Beth Flanagan, Christiana Lakey and Mark, Scott, Lynn and Melissa Taylor.

Chapter I THE BLESSED COMMUNITY:

Quakerism: a view from the back benches

Copyright 1966 The Back Benches

Chapter ICopyright 1966 The Back Benches

THE BLESSED COMMUNITY:

What are we mything?

We believe that many of the ills of Quakerism today are reflected in the breakdown of sharing and caring among the members. Or is it better to say that the lack of community, which we deeply feel, has caused the ills of the Society?

Obviously, we are faced with a chicken-egg situation in which cause and effect may seem hopelessly blurred. Laying aside Quaker prudence for the nonce, we here cast our lot with the chicken, and say that we believe that the drying-up of community in the Society of Friends is cause by the lack of common purpose among members and a fantastically wide variety of attitudes on what it means to be a Quaker. Hence, if I believe that my Quakerism means that, as a respected member of the middle class, I prefer to reflect my Christianity on Sunday morning in silence rather than genuflection, I can hardly be expected to communicate will with you, if you insist that your Quakerism has required you to break a law for conscience’s sake and spend the night in jail. We may be expected to sit in silence together for an hour, but can we be expected truly to share that brief experience, let alone our very lives the rest of the week? Can I be expected to wear my Quaker habit comfortably when your witness has branded all Quakers in our town as civil-disobedient? And do I detect an accusation of weakness in your Sunday morning hand-shake? How can we live together in the Society, loving, sharing, communicating, when the Light of Truth reveals to us such different requirements for our lives?

The Quaker belief that God can reveal his will directly to each of us if we can but learn to listen is the undergirding of our religious faith. Paradoxically, the belief poses for us a dilemma of staggering proportions. How can we dwell together in love and community when we are free to follow divergent paths?

We believe that there are some practical devices which- if we care enough- we can diligently employ to open the way for a recreation of a beloved community in our Society, in our various Monthly Meetings.

Obviously, we are faced with a chicken-egg situation in which cause and effect may seem hopelessly blurred. Laying aside Quaker prudence for the nonce, we here cast our lot with the chicken, and say that we believe that the drying-up of community in the Society of Friends is cause by the lack of common purpose among members and a fantastically wide variety of attitudes on what it means to be a Quaker. Hence, if I believe that my Quakerism means that, as a respected member of the middle class, I prefer to reflect my Christianity on Sunday morning in silence rather than genuflection, I can hardly be expected to communicate will with you, if you insist that your Quakerism has required you to break a law for conscience’s sake and spend the night in jail. We may be expected to sit in silence together for an hour, but can we be expected truly to share that brief experience, let alone our very lives the rest of the week? Can I be expected to wear my Quaker habit comfortably when your witness has branded all Quakers in our town as civil-disobedient? And do I detect an accusation of weakness in your Sunday morning hand-shake? How can we live together in the Society, loving, sharing, communicating, when the Light of Truth reveals to us such different requirements for our lives?

The Quaker belief that God can reveal his will directly to each of us if we can but learn to listen is the undergirding of our religious faith. Paradoxically, the belief poses for us a dilemma of staggering proportions. How can we dwell together in love and community when we are free to follow divergent paths?

We believe that there are some practical devices which- if we care enough- we can diligently employ to open the way for a recreation of a beloved community in our Society, in our various Monthly Meetings.

The Size of the Meeting

Quakerism: a view from the back benches

Copyright 1966 The Back Benches

The Size of the Meeting

Experience leads us to the conclusion that the number of people attempting to create a religious community is the determining factor in success. The large, urban Meeting, while offering an intricate, often well-functioning organization with something for everyone, is not the breeding ground for total commitment of its members. It is true that individuals can commit themselves to work in such a Meeting, but the prospect is that they will limit their activities to certain compartments within the Meeting. This may be satisfying to individuals in the short run but, in the long run, may be destructive of the possibilities for corporate activity and growth.

Many members of large Meetings recognize this problem yet resist addressing themselves to a solution. Tradition, the care of a much-loved meeting house, a graveyard, a school, an old people’s home, etc., still the voices of those who might otherwise face up to the need for experimentation in size. The effect of Meeting property on the Quaker religious life is dealt with in another chapter. Here, we will only state that large holdings of property can crush the vitality of a Meeting’s active workers, frighten them in rigidity concerning change,and transform an experiential religion into an institution.

Large urban Meetings need to face squarely the need for growth-by-division. Ideas of what constitutes the correct size may vary; if a large urban Meeting were to multiply into a series of House Meetings, 15 to 30 adults might be a good number. Rotation of the place of Meeting (homes) would not unduly burden members; and finances would relate directly to the concerns of the Meeting and contributions might be more cheerfully given than is often the case in large membership organizations.

Leaving the newly constituted “House Quakers” for the moment, let us consider the problems of the too-small Meeting. It is safe to say that American Quakerism boasts many Meetings with too few members valiantly struggling to keep the Meeting alive in order to preserve a tradition, a lovely old meeting house, and so forth. Respecting these motivations as admirable and intensely human, we yet feel tender toward the admirable and intensely human, we yet may feel tender toward the needs of the Friends who so labor, and we question whether these burdens allow for the fullest participation in the wider and deeper Quaker experience.

An attempt by these members of identify what is of real value to them in these small, struggling Meetings and sift out what is merely burden may be of help. Perhaps the real essence, for example, will be found to be a meaningful worship, or a regular fellowship supper, or a children’s educational activity. This valued activity might be made vital by dispensing with all else in the Meeting’s life.

Perhaps, finally, the solution would be to lay down the Meeting or to join with another neighboring Meeting which shares many of the same difficulties of survival. The test would be whether by such experiments release and renewal are found by members, giving rise to fuller participation in Friendly concerns, and a more productive worship experience for all.

Perhaps small Meetings might spring up around a specific concern, such as a mental hospital, prison, peace effort, etc., so that the life a the Meeting would be focused on one area, at least for a time, all members giving and gaining spiritual sustenance through this unity of concern. If such a Meeting is later laid down, Friends are cautioned not to mourn its passing but to rejoice in the quality of service and spirit which it possessed while it was alive.

In smaller, closer Meetings, there is more possibility for experiment in new forms of communication, such as music, drama, the dance, and common work. New adjuncts to worship could be developed, predicated on the theory that silence is not sacrosanct, having no inherent life or value of its own, but is made meaningful by those who share it. Experimentation with new ways of creating a silence alive with communicated truth should not be considered heretical so long as the effort is serious, focused on a goal, flexible, and above all fruitful.

Copyright 1966 The Back Benches

The Size of the Meeting

Experience leads us to the conclusion that the number of people attempting to create a religious community is the determining factor in success. The large, urban Meeting, while offering an intricate, often well-functioning organization with something for everyone, is not the breeding ground for total commitment of its members. It is true that individuals can commit themselves to work in such a Meeting, but the prospect is that they will limit their activities to certain compartments within the Meeting. This may be satisfying to individuals in the short run but, in the long run, may be destructive of the possibilities for corporate activity and growth.

Many members of large Meetings recognize this problem yet resist addressing themselves to a solution. Tradition, the care of a much-loved meeting house, a graveyard, a school, an old people’s home, etc., still the voices of those who might otherwise face up to the need for experimentation in size. The effect of Meeting property on the Quaker religious life is dealt with in another chapter. Here, we will only state that large holdings of property can crush the vitality of a Meeting’s active workers, frighten them in rigidity concerning change,and transform an experiential religion into an institution.

Large urban Meetings need to face squarely the need for growth-by-division. Ideas of what constitutes the correct size may vary; if a large urban Meeting were to multiply into a series of House Meetings, 15 to 30 adults might be a good number. Rotation of the place of Meeting (homes) would not unduly burden members; and finances would relate directly to the concerns of the Meeting and contributions might be more cheerfully given than is often the case in large membership organizations.

Leaving the newly constituted “House Quakers” for the moment, let us consider the problems of the too-small Meeting. It is safe to say that American Quakerism boasts many Meetings with too few members valiantly struggling to keep the Meeting alive in order to preserve a tradition, a lovely old meeting house, and so forth. Respecting these motivations as admirable and intensely human, we yet feel tender toward the admirable and intensely human, we yet may feel tender toward the needs of the Friends who so labor, and we question whether these burdens allow for the fullest participation in the wider and deeper Quaker experience.

An attempt by these members of identify what is of real value to them in these small, struggling Meetings and sift out what is merely burden may be of help. Perhaps the real essence, for example, will be found to be a meaningful worship, or a regular fellowship supper, or a children’s educational activity. This valued activity might be made vital by dispensing with all else in the Meeting’s life.

Perhaps, finally, the solution would be to lay down the Meeting or to join with another neighboring Meeting which shares many of the same difficulties of survival. The test would be whether by such experiments release and renewal are found by members, giving rise to fuller participation in Friendly concerns, and a more productive worship experience for all.

Perhaps small Meetings might spring up around a specific concern, such as a mental hospital, prison, peace effort, etc., so that the life a the Meeting would be focused on one area, at least for a time, all members giving and gaining spiritual sustenance through this unity of concern. If such a Meeting is later laid down, Friends are cautioned not to mourn its passing but to rejoice in the quality of service and spirit which it possessed while it was alive.

In smaller, closer Meetings, there is more possibility for experiment in new forms of communication, such as music, drama, the dance, and common work. New adjuncts to worship could be developed, predicated on the theory that silence is not sacrosanct, having no inherent life or value of its own, but is made meaningful by those who share it. Experimentation with new ways of creating a silence alive with communicated truth should not be considered heretical so long as the effort is serious, focused on a goal, flexible, and above all fruitful.

Caring and Sharing

Quakerism: a view from the back benches

Copyright 1966 The Back Benches

Caring and Sharing

The smaller, closer Meeting automatically presents the question of how best to share the burdens of troubled members. Aside from the normal troubles and sorrows which beset each of us from time to time, Quakerism seems to attract a number of people with real emotional disturbances and mental illnesses. How can a Meeting support these members without being sapped and fractured by the sometimes almost overwhelming burden?

The first commitment must be in our attitude toward the Meeting. To do anything at all, we must first be willing to assign to the Meeting a vital role as a primary in-group to which each member can relate for love and security, second only, perhaps, to the family.

As a primary in-group the Meeting becomes a major focus of life for its members for the length of time that it exists; and it must devise ways to respond creatively and constructively to the needs of individuals. To survive under the weight of these needs, we believe the Meeting must supply a warm, supportive atmosphere, responsive to troubled members but determined to share collective joys as well as miseries. While being sensitive and tender, the atmosphere must be in some degree buoyant, joyous, making use of the great store of gentle humor to be found among Friends.

While caring for its emotionally disturbed members, the Meeting which allows these members constantly to use is time together, whether it be worship, business or social, for personal therapy is headed for trouble, is not likely to help the member in trouble, and is liable to a feeling of being put-upon. The Meeting should know its limitations in this regard and stand ready to guide members to professional help when indicated, either from within or without the Meeting membership.

A Meeting which provides an emotional tie will be the natural place for bringing matters for advice which are now called “personal” - job changes, school choices, marital difficulties. The ultimate step in the relationship between a member and his Meeting comes when the member moves away; consequently, such a move will be a matter of weighty consideration by the member, consulting with the Meeting.

Another facet of the “caring” responsibility of Meetings is the frequent need to free individual members who have a clear leading to act on a concern. The Meeting should be ready and willing to meet the practical needs of a Friend and his family who is under the weight of a Quaker concern, but whose practical necessities may make it impossible for him to give time and full attention to carrying out such a concern.

Copyright 1966 The Back Benches

Caring and Sharing

The smaller, closer Meeting automatically presents the question of how best to share the burdens of troubled members. Aside from the normal troubles and sorrows which beset each of us from time to time, Quakerism seems to attract a number of people with real emotional disturbances and mental illnesses. How can a Meeting support these members without being sapped and fractured by the sometimes almost overwhelming burden?

The first commitment must be in our attitude toward the Meeting. To do anything at all, we must first be willing to assign to the Meeting a vital role as a primary in-group to which each member can relate for love and security, second only, perhaps, to the family.

As a primary in-group the Meeting becomes a major focus of life for its members for the length of time that it exists; and it must devise ways to respond creatively and constructively to the needs of individuals. To survive under the weight of these needs, we believe the Meeting must supply a warm, supportive atmosphere, responsive to troubled members but determined to share collective joys as well as miseries. While being sensitive and tender, the atmosphere must be in some degree buoyant, joyous, making use of the great store of gentle humor to be found among Friends.

While caring for its emotionally disturbed members, the Meeting which allows these members constantly to use is time together, whether it be worship, business or social, for personal therapy is headed for trouble, is not likely to help the member in trouble, and is liable to a feeling of being put-upon. The Meeting should know its limitations in this regard and stand ready to guide members to professional help when indicated, either from within or without the Meeting membership.

A Meeting which provides an emotional tie will be the natural place for bringing matters for advice which are now called “personal” - job changes, school choices, marital difficulties. The ultimate step in the relationship between a member and his Meeting comes when the member moves away; consequently, such a move will be a matter of weighty consideration by the member, consulting with the Meeting.

Another facet of the “caring” responsibility of Meetings is the frequent need to free individual members who have a clear leading to act on a concern. The Meeting should be ready and willing to meet the practical needs of a Friend and his family who is under the weight of a Quaker concern, but whose practical necessities may make it impossible for him to give time and full attention to carrying out such a concern.

Towards Unity

Quakerism: a view from the back benches

Copyright 1966 The Back Benches

Towards Unity

Something has been said above about the need for a daring reappraisal of what membership in the Society of Friends means to members. Here we will probe the question of what membership requires. At present, we believe that most Meetings ( the few exceptions being barley adequate to prove the rule ) have no requirements for membership other than some accepted patterns of application, visitation and the like. It is safe to say that denials on any basis are rare, and more likely to occur on grounds other than the applicants religious conviction or position on Quaker testimonies. To press the point further, we can say there is at present an unwillingness among Friends to deal with these matters with prospective members, because to attempt this would necessitate the Meeting undertaking to arrive at unity on these thorny questions in the first place.

We maintain that Friends must do just that if they care about their Meetings communities. That is, they must (1) seek unity on what the requirements of membership should be, in a series of called special meetings to thresh out the matter, (2) apply these requirements to themselves, and (3) use them in the examination and acceptance of new members. Open now to the cries of wounded sensitivities regarding loss of freedom, we take shelter beside (critics may say "behind") George Fox, who did outline stringent requirements for adherents to the Light, and in whose time Quakerism was at its most potent and vital. If Friends cling to their faith that truth can be revealed to the faithful searcher, they need not fear to undertake the search, no matter how long and arduous it may be. The result may be a minimal definition. Conversely, who among us can say that a search undertaken in love and patience will not reveal to us a new requirement, not presently known to us singly?

Supposing that unity has been found on requirements of membership, but frankness compels us to admit that some members have more light on certain testimonies than others. Can we then submit ourselves to discipline by the corporate body, employing a new form of the historic Quaker practice of "eldering?" Can we redefine this proactive to remove the modern connotation of reprimand, expand it beyond the current meaning of controlling disruptive ministry in worship, and coin a new term which would carry the concept of mutual sharing of insight to achieve unity? We might call it "insight sharing" or "mutualizing." The reader who is interested in this suggestion will no doubt devise a more apt term.

This practice used today - as in Quaker history - would ask members to share their clarity on various testimonies with their fellow members. For example, if a Meeting has reached a corporate decision that a modern requirement of the testimony on brotherhood is a willingness to sell one’s house to a Negro, a Friend who feels clear on this testimony will be asked to labor with one who is not; he will be speaking for the corporate body, drawing on his own revelation in the matter, and strengthened by the knowledge that he is advancing he Meeting’s work.. Under this practice, this same Friend may find himself unclear on another of the testimonies united on by the Meeting and thus be the object of the Meeting’s concern and attention. Hence, the "mutual" aspect of this practice historically known as eldering may bring it up to the present day.

Having come through this task, the Meeting may then be free to communicate its requirements to prospective embers and to set up certain programs to help attenders make considered decisions regarding their relation to the Society. For example, a systematic course of study can be offered, responsibilities outlined, readiness for membership reasonably assessed by the applicant as well as the Meeting. This will help avoid resignations based on an original misunderstanding of what " a Quaker" is.

What safeguard in this arduous procedure against the dreaded dogmatic, creedal system? It is, again built into the Quaker method of arriving at decisions. Functioning properly, Friends can bring out all differences, all points of view on a problem and gain not just consensus, but Truth. We must accept the fact that perception of Truth may divide as well as unite us as a Meeting. If it unties us, it will strengthen us; if it splits us, we should have the courage to follow where the Truth leads us.

The suggestions set forth here as ways to vitalize community in the Society of Friends are not offered as brand new, heretofore-unthought-of techniques. Concerned Friends have no doubt ruminated over these and other, even better, ideas time and time again. The only possible novelty here is that we openly propose that Meetings test these ideas by use, with no guarantees of absolute success; but with insurance against absolute failure resting in the inevitable enlargement of self-knowledge, deeper awareness of others, and exercise of faith in the Light by which we seek to find the way.

Copyright 1966 The Back Benches

Towards Unity

Something has been said above about the need for a daring reappraisal of what membership in the Society of Friends means to members. Here we will probe the question of what membership requires. At present, we believe that most Meetings ( the few exceptions being barley adequate to prove the rule ) have no requirements for membership other than some accepted patterns of application, visitation and the like. It is safe to say that denials on any basis are rare, and more likely to occur on grounds other than the applicants religious conviction or position on Quaker testimonies. To press the point further, we can say there is at present an unwillingness among Friends to deal with these matters with prospective members, because to attempt this would necessitate the Meeting undertaking to arrive at unity on these thorny questions in the first place.

We maintain that Friends must do just that if they care about their Meetings communities. That is, they must (1) seek unity on what the requirements of membership should be, in a series of called special meetings to thresh out the matter, (2) apply these requirements to themselves, and (3) use them in the examination and acceptance of new members. Open now to the cries of wounded sensitivities regarding loss of freedom, we take shelter beside (critics may say "behind") George Fox, who did outline stringent requirements for adherents to the Light, and in whose time Quakerism was at its most potent and vital. If Friends cling to their faith that truth can be revealed to the faithful searcher, they need not fear to undertake the search, no matter how long and arduous it may be. The result may be a minimal definition. Conversely, who among us can say that a search undertaken in love and patience will not reveal to us a new requirement, not presently known to us singly?

Supposing that unity has been found on requirements of membership, but frankness compels us to admit that some members have more light on certain testimonies than others. Can we then submit ourselves to discipline by the corporate body, employing a new form of the historic Quaker practice of "eldering?" Can we redefine this proactive to remove the modern connotation of reprimand, expand it beyond the current meaning of controlling disruptive ministry in worship, and coin a new term which would carry the concept of mutual sharing of insight to achieve unity? We might call it "insight sharing" or "mutualizing." The reader who is interested in this suggestion will no doubt devise a more apt term.

This practice used today - as in Quaker history - would ask members to share their clarity on various testimonies with their fellow members. For example, if a Meeting has reached a corporate decision that a modern requirement of the testimony on brotherhood is a willingness to sell one’s house to a Negro, a Friend who feels clear on this testimony will be asked to labor with one who is not; he will be speaking for the corporate body, drawing on his own revelation in the matter, and strengthened by the knowledge that he is advancing he Meeting’s work.. Under this practice, this same Friend may find himself unclear on another of the testimonies united on by the Meeting and thus be the object of the Meeting’s concern and attention. Hence, the "mutual" aspect of this practice historically known as eldering may bring it up to the present day.

Having come through this task, the Meeting may then be free to communicate its requirements to prospective embers and to set up certain programs to help attenders make considered decisions regarding their relation to the Society. For example, a systematic course of study can be offered, responsibilities outlined, readiness for membership reasonably assessed by the applicant as well as the Meeting. This will help avoid resignations based on an original misunderstanding of what " a Quaker" is.

What safeguard in this arduous procedure against the dreaded dogmatic, creedal system? It is, again built into the Quaker method of arriving at decisions. Functioning properly, Friends can bring out all differences, all points of view on a problem and gain not just consensus, but Truth. We must accept the fact that perception of Truth may divide as well as unite us as a Meeting. If it unties us, it will strengthen us; if it splits us, we should have the courage to follow where the Truth leads us.

The suggestions set forth here as ways to vitalize community in the Society of Friends are not offered as brand new, heretofore-unthought-of techniques. Concerned Friends have no doubt ruminated over these and other, even better, ideas time and time again. The only possible novelty here is that we openly propose that Meetings test these ideas by use, with no guarantees of absolute success; but with insurance against absolute failure resting in the inevitable enlargement of self-knowledge, deeper awareness of others, and exercise of faith in the Light by which we seek to find the way.

Chapter II FAITH AND PRACTICE

Quakerism: a view from the back benches

Copyright 1966 The Back Benches

Chapter II

Introduction:

The testimonies of Friends grew out of the ethical insights provided by the Inner Light and by New Testament teachings, as they seemed relevant to 17th century England. The word "Testimony" can be significant, for the idea was not that Friends should testify to them, inherent in the concept is action as well as belief.

In a time when it is possible for a long-time best-seller to be called "The Power of Positive Thinking," some people are disturbed because the testimonies are often put in a negative way. Perhaps they are so put because of the action aspect of the testimony, and the effort, through the queries, to measure in a rough way the degree to which Friends are actually testifying. One can see the difference by putting a testimony in these two ways:

"Do Friends love their Negro brothers?"

"Are Friends clear of slave-holding?"

There is a precision about action which is lacking in attitude, for the purpose of corporate soul-searching. It was, after all, for the purpose of corporate soul-searching that the queries were designed, with the answers being sent up to Yearly Meeting for its disciplinary action.

Their original purpose has been all but lost sight of, and the queries function now as a ritualistic Quaker equivalent of the Ten Commandments. As with the Commandments, the queries do not gain in effect with repetition, and if Friends really want their faces splashed with the cold water of ethical challenge, we should recommend that the queries be rephrased in blunt modern language.

Language is always a problem in religious circles, and we are not exceptions. Early Friends did call a spade a spade, and a church a steeple house. We wonder whether the very word "testimony" gets in the way of challenge by connoting some quaintness which individuals can take or leave.

We should preface our examination of the testimonies with the caution that we speak out of somewhat limited experience, and are bereft of scientific studies which would reveal what the state of the testimonies actually is. Our comments are, therefore, impressionistic. We enlist the reader in our effort to be severely honest, and hope that he will not be so interested in defending his image in our Society that he will refuse to examine objectively the state of the testimonies in his own Meeting and among his acquaintances.

Copyright 1966 The Back Benches

Chapter II

FAITH AND PRACTICE

The Dichotomy Revisited

The Dichotomy Revisited

Introduction:

The testimonies of Friends grew out of the ethical insights provided by the Inner Light and by New Testament teachings, as they seemed relevant to 17th century England. The word "Testimony" can be significant, for the idea was not that Friends should testify to them, inherent in the concept is action as well as belief.

In a time when it is possible for a long-time best-seller to be called "The Power of Positive Thinking," some people are disturbed because the testimonies are often put in a negative way. Perhaps they are so put because of the action aspect of the testimony, and the effort, through the queries, to measure in a rough way the degree to which Friends are actually testifying. One can see the difference by putting a testimony in these two ways:

"Do Friends love their Negro brothers?"

"Are Friends clear of slave-holding?"

There is a precision about action which is lacking in attitude, for the purpose of corporate soul-searching. It was, after all, for the purpose of corporate soul-searching that the queries were designed, with the answers being sent up to Yearly Meeting for its disciplinary action.

Their original purpose has been all but lost sight of, and the queries function now as a ritualistic Quaker equivalent of the Ten Commandments. As with the Commandments, the queries do not gain in effect with repetition, and if Friends really want their faces splashed with the cold water of ethical challenge, we should recommend that the queries be rephrased in blunt modern language.

Language is always a problem in religious circles, and we are not exceptions. Early Friends did call a spade a spade, and a church a steeple house. We wonder whether the very word "testimony" gets in the way of challenge by connoting some quaintness which individuals can take or leave.

We should preface our examination of the testimonies with the caution that we speak out of somewhat limited experience, and are bereft of scientific studies which would reveal what the state of the testimonies actually is. Our comments are, therefore, impressionistic. We enlist the reader in our effort to be severely honest, and hope that he will not be so interested in defending his image in our Society that he will refuse to examine objectively the state of the testimonies in his own Meeting and among his acquaintances.

The Hireling Ministry (Let George Do It)

Quakerism: a view from the back benches

Copyright 1966 The Back Benches

The Hireling Ministry (Let George Do It)

Friends have from the beginning felt a distrust of a separate ministry. The Light was in all, and children might be (and were) called to preach, women might be moved to travel long distances in journeys of reconciliation, or agitation, and everyone had a responsibility for spiritual and social work.

We have probably been one of the most successful religious groups in history at maintaining this practice. But the writers of this study, looking about at the growth of Quaker agencies of all kinds, not the phenomenon of the ‘professional Quaker” - a person who, because of his gifts, is hired on a virtually permanent basis to perform a ministry of some kind. Corresponding to this is, we sense, a growing willingness for “rank-and-file” Friends to consider their financial contributions to these agencies as an adequate total participation in the concerns of the Society.

We recognize that this is partly in response to the tensing of our society: it is more difficult to have a career as a professional without investing exorbitant amounts of time in it; in business one either “gets ahead” or gets out; the ability to get away for a couple of years in Quaker service is becoming rarer for people of our general social-economic level.Recognizing the problem may enable us to take some steps towards its amelioration: Friends agencies might hire only those who have not been employed before in Quaker organization; such agencies might establish strict policies against long-time employment of the same person; every Friend might be strongly encouraged to give one or more years of his working career to a Friends organization, either before beginning his professional career or after retiring from it, much as Peace Corps people are doing.

If there were such a genuinely rotating system of opportunity for service, the Quaker agencies might be giving valuable experience which would then be plowed back into Monthly Meeting life.

Copyright 1966 The Back Benches

The Hireling Ministry (Let George Do It)

Friends have from the beginning felt a distrust of a separate ministry. The Light was in all, and children might be (and were) called to preach, women might be moved to travel long distances in journeys of reconciliation, or agitation, and everyone had a responsibility for spiritual and social work.

We have probably been one of the most successful religious groups in history at maintaining this practice. But the writers of this study, looking about at the growth of Quaker agencies of all kinds, not the phenomenon of the ‘professional Quaker” - a person who, because of his gifts, is hired on a virtually permanent basis to perform a ministry of some kind. Corresponding to this is, we sense, a growing willingness for “rank-and-file” Friends to consider their financial contributions to these agencies as an adequate total participation in the concerns of the Society.

We recognize that this is partly in response to the tensing of our society: it is more difficult to have a career as a professional without investing exorbitant amounts of time in it; in business one either “gets ahead” or gets out; the ability to get away for a couple of years in Quaker service is becoming rarer for people of our general social-economic level.Recognizing the problem may enable us to take some steps towards its amelioration: Friends agencies might hire only those who have not been employed before in Quaker organization; such agencies might establish strict policies against long-time employment of the same person; every Friend might be strongly encouraged to give one or more years of his working career to a Friends organization, either before beginning his professional career or after retiring from it, much as Peace Corps people are doing.

If there were such a genuinely rotating system of opportunity for service, the Quaker agencies might be giving valuable experience which would then be plowed back into Monthly Meeting life.

Race Relations ( a Whiter Quaker Fellowship?)

Quakerism: a view from the back benches

Copyright 1966 The Back Benches

Race Relations ( a Whiter Quaker Fellowship?)

Our Society is not in unity on our testimony on race relations: honesty insists that we admit that we do not yet all agree on full brotherhood. Our testimony against slave-holding was a brave and wonderful thing, once, but we have been living off the spiritual capital there for a long time, and our bookkeeping is so poor that we scarcely now know that we are in debt to the Negroes who might possibly at one time have acknowledged a debt to us.

The stories are endless. There is the Meeting which turned away Negroes on Brotherhood Sunday; there is the Quaker old folks home which openly advertised “For Whites Only;” there is the Quaker college which was integrated only by the Armed Forces; and there are the Quaker Schools which are barely integrated yet.

Our stand-offish attitudes have so cut us off from the Negro community that most Friends do not know how to begin to understand the revolution for human dignity today. Some of our young Friends would like the Society to join the revolution. But how can we, if we do not even know why it is occurring?Once Friends knew the bitterness of discrimination. Now we are welcomed.

Once Friends knew the anxiety of poverty. Now we are privileged. Once Friends knew the desperation of the powerless. Now we are, many of us, powerful in our communities. Could this be the root of it?Our continuing concern for Negroes has been for them as individuals. Homes and orphanages were set up by Friends, schools and colleges, social agencies for the colored. We do not mean to minimize the work, the pioneering, and the danger represented by some of these efforts. But the focus was always on the individual casualties of our society and not on the institutions which create the casualties.

Whatever the reason, a number of religious groups are far ahead of Friends in the practice of brotherhood, and we should be thankful for a lesson in humility. We need to ask God for forgiveness and cease our segregated practices. We need to join the revolution for human dignity by throwing our political and economic weight behind extensive social change of the conditions of American Life which breed ghettos and discrimination. At the same time, we must accept interracial marriage, the adoption of children of mixed background, and the fact that our Negro Friends are simply members of our Society who need feel no obligation to be “official Negroes.”The time has come for another look at Quaker work with the Indians as well. Are we, here too, relying on casework and mission approaches to a problem which is political and economic in its nature? When will we press in nonviolent but powerful ways for the rights of the American Indians?

Copyright 1966 The Back Benches

Race Relations ( a Whiter Quaker Fellowship?)

Our Society is not in unity on our testimony on race relations: honesty insists that we admit that we do not yet all agree on full brotherhood. Our testimony against slave-holding was a brave and wonderful thing, once, but we have been living off the spiritual capital there for a long time, and our bookkeeping is so poor that we scarcely now know that we are in debt to the Negroes who might possibly at one time have acknowledged a debt to us.

The stories are endless. There is the Meeting which turned away Negroes on Brotherhood Sunday; there is the Quaker old folks home which openly advertised “For Whites Only;” there is the Quaker college which was integrated only by the Armed Forces; and there are the Quaker Schools which are barely integrated yet.

Our stand-offish attitudes have so cut us off from the Negro community that most Friends do not know how to begin to understand the revolution for human dignity today. Some of our young Friends would like the Society to join the revolution. But how can we, if we do not even know why it is occurring?Once Friends knew the bitterness of discrimination. Now we are welcomed.

Once Friends knew the anxiety of poverty. Now we are privileged. Once Friends knew the desperation of the powerless. Now we are, many of us, powerful in our communities. Could this be the root of it?Our continuing concern for Negroes has been for them as individuals. Homes and orphanages were set up by Friends, schools and colleges, social agencies for the colored. We do not mean to minimize the work, the pioneering, and the danger represented by some of these efforts. But the focus was always on the individual casualties of our society and not on the institutions which create the casualties.

Whatever the reason, a number of religious groups are far ahead of Friends in the practice of brotherhood, and we should be thankful for a lesson in humility. We need to ask God for forgiveness and cease our segregated practices. We need to join the revolution for human dignity by throwing our political and economic weight behind extensive social change of the conditions of American Life which breed ghettos and discrimination. At the same time, we must accept interracial marriage, the adoption of children of mixed background, and the fact that our Negro Friends are simply members of our Society who need feel no obligation to be “official Negroes.”The time has come for another look at Quaker work with the Indians as well. Are we, here too, relying on casework and mission approaches to a problem which is political and economic in its nature? When will we press in nonviolent but powerful ways for the rights of the American Indians?

Peace (No Cross, No Crown, No Nothing)

Quakerism: a view from the back benches

Copyright 1966 The Back Benches

Peace (No Cross, No Crown, No Nothing)

The peace testimony has been in many ways the glory of Quakerism; it has more than other factor preserved us from the idolatry of nationalism. Since nationalism is most conspicuous and most demanding during wartime, our refusal of military participation enabled us to retain some modicum of objectivity when others were drowning in a sea of subjective patriotism.

It is our impression, however, that the peace testimony is not very strong. Certainly the number of young men becoming conscientious objectors is small. There are Meetings where an applicant for membership is not even asked his convictions on war and peace. One can hear the scantiest and most simple-minded arguments from young army-bound Quakers, indicating that their Meetings have not pressed them to develop even an informed non-pacifist position. Indeed, there are Meetings where the burden of argument is upon the lad is a pacifist, and where the adults accept in a naïve way the State Department line and the jingoist newspaper accounts.

These developments, plus the emergence of Quaker members in the John Birch Society, indicate that nationalism is gaining ground. Peace-concerned Quakers are sometimes upbraided for sounding “unpatriotic” when they call a spade a spade - an atrocity an atrocity. The idea that the American nation-state-like all great powers-is capable of gross immoralities meets with increasing Quaker resistance because our emotional ties are growing stronger to our country. To criticize the government is increasingly to criticize us, at the same time that one hears members of the Society refer to Friends in general as “they.” What is happening but a shift of emotional identification in which one’s religious commitment no longer gives one an objective position from which to judge the behavior of one’s government?

We deeply believe that this is no peripheral issue: this is nothing to shrug off with a murmur about “each to his own light,” This issue goes to the very heart of the continued existence of the Society of Friends as anything like a genuine religious community. When a religious commitment can no longer protect one from the claims of class, of color, or of country, that commitment is nothing but the shadow of piety: it was such that George Fox scorned.

It seems essential, therefore, that no one be admitted to membership who does not intend to refrain from violence against other men. We suggest, too, that by 1975 all present members should be clear that violence is evil and is not justified able under any circumstances. While coming to accept this basic principle, we must develop creative responses to violence, so that our pacifism cannot be a cover for indifference to the claims of justice. The insights of those Friends who do not presently call themselves pacifists will be valued as we engage in this exercise of clarity.

Copyright 1966 The Back Benches

Peace (No Cross, No Crown, No Nothing)

The peace testimony has been in many ways the glory of Quakerism; it has more than other factor preserved us from the idolatry of nationalism. Since nationalism is most conspicuous and most demanding during wartime, our refusal of military participation enabled us to retain some modicum of objectivity when others were drowning in a sea of subjective patriotism.

It is our impression, however, that the peace testimony is not very strong. Certainly the number of young men becoming conscientious objectors is small. There are Meetings where an applicant for membership is not even asked his convictions on war and peace. One can hear the scantiest and most simple-minded arguments from young army-bound Quakers, indicating that their Meetings have not pressed them to develop even an informed non-pacifist position. Indeed, there are Meetings where the burden of argument is upon the lad is a pacifist, and where the adults accept in a naïve way the State Department line and the jingoist newspaper accounts.

These developments, plus the emergence of Quaker members in the John Birch Society, indicate that nationalism is gaining ground. Peace-concerned Quakers are sometimes upbraided for sounding “unpatriotic” when they call a spade a spade - an atrocity an atrocity. The idea that the American nation-state-like all great powers-is capable of gross immoralities meets with increasing Quaker resistance because our emotional ties are growing stronger to our country. To criticize the government is increasingly to criticize us, at the same time that one hears members of the Society refer to Friends in general as “they.” What is happening but a shift of emotional identification in which one’s religious commitment no longer gives one an objective position from which to judge the behavior of one’s government?

We deeply believe that this is no peripheral issue: this is nothing to shrug off with a murmur about “each to his own light,” This issue goes to the very heart of the continued existence of the Society of Friends as anything like a genuine religious community. When a religious commitment can no longer protect one from the claims of class, of color, or of country, that commitment is nothing but the shadow of piety: it was such that George Fox scorned.

It seems essential, therefore, that no one be admitted to membership who does not intend to refrain from violence against other men. We suggest, too, that by 1975 all present members should be clear that violence is evil and is not justified able under any circumstances. While coming to accept this basic principle, we must develop creative responses to violence, so that our pacifism cannot be a cover for indifference to the claims of justice. The insights of those Friends who do not presently call themselves pacifists will be valued as we engage in this exercise of clarity.

Quaker Education (Myth or Reality)

Quakerism: a view from the back benches

Copyright 1966 The Back Benches

Quaker Education (Myth or Reality)

It is difficult to generalize about Quaker education. We see many Quaker Schools which are like nothing so much as decent public or private schools; one strains to see anything about them besides the name which would stamp them as Quaker. The Children may hear a little more about good will, but not about pacifism; they often see fewer disadvantaged children than they would in public schools, thus being deprived of a variety of experience and friendship,; they learn how dull silence can be and achieve a certain discipline in its endurance.

On the other hand, there are Quaker schools which are boldly innovative; which put into practice the idea that children can heed the Inward Light, and can act responsibly; which challenge them with the full weight and excitement of Quaker testimonies.

One reason early Friends set up schools was to provide a “guarded education” - a protective atmosphere where the children of a particular people could remain unsoiled by unnecessary contact with the world. This idea is all but dead in Quaker education.

A second idea which led to founding schools was that of offering education to those who would otherwise not have the opportunity, there being no public schools.

Lacking these impulses, the question becomes: Is there really a Quaker theory of education? Some of the undersigned do not think so and believe the schools should be laid down or given away. The Meetings could better use the money for scholarships for work camps, summer institutes, and other forms of dynamic Quaker activity which is testimony-centered. In our concern for non-Quaker children, some of us believe that Quaker time and energy on public school boards and in public pressure groups cold bring quality education to more children than can a Friends school, and be more suitably spread. It is hard to justify the idea that well-to-do children who can afford Quaker school tuition deserve quality education more than the poor.

Others of the undersigned feel that Friends schools could do some extraordinary things which other schools cannot do as easily but this would probably require: (1) faculties composed of Friends, (2) higher proportion of Quaker children, (3) a move closer to the ghetto and away from the suburbs, (4) substantial scholarship aid so that quality education can be offered to those who need it most, (5) daringly experimental approaches to educational methods, (6) a reorientation of goals away from “the percentage place in name-brand colleges” to “ the percentage dedicating themselves to lives of service.”

Copyright 1966 The Back Benches

Quaker Education (Myth or Reality)

It is difficult to generalize about Quaker education. We see many Quaker Schools which are like nothing so much as decent public or private schools; one strains to see anything about them besides the name which would stamp them as Quaker. The Children may hear a little more about good will, but not about pacifism; they often see fewer disadvantaged children than they would in public schools, thus being deprived of a variety of experience and friendship,; they learn how dull silence can be and achieve a certain discipline in its endurance.

On the other hand, there are Quaker schools which are boldly innovative; which put into practice the idea that children can heed the Inward Light, and can act responsibly; which challenge them with the full weight and excitement of Quaker testimonies.

One reason early Friends set up schools was to provide a “guarded education” - a protective atmosphere where the children of a particular people could remain unsoiled by unnecessary contact with the world. This idea is all but dead in Quaker education.

A second idea which led to founding schools was that of offering education to those who would otherwise not have the opportunity, there being no public schools.

Lacking these impulses, the question becomes: Is there really a Quaker theory of education? Some of the undersigned do not think so and believe the schools should be laid down or given away. The Meetings could better use the money for scholarships for work camps, summer institutes, and other forms of dynamic Quaker activity which is testimony-centered. In our concern for non-Quaker children, some of us believe that Quaker time and energy on public school boards and in public pressure groups cold bring quality education to more children than can a Friends school, and be more suitably spread. It is hard to justify the idea that well-to-do children who can afford Quaker school tuition deserve quality education more than the poor.

Others of the undersigned feel that Friends schools could do some extraordinary things which other schools cannot do as easily but this would probably require: (1) faculties composed of Friends, (2) higher proportion of Quaker children, (3) a move closer to the ghetto and away from the suburbs, (4) substantial scholarship aid so that quality education can be offered to those who need it most, (5) daringly experimental approaches to educational methods, (6) a reorientation of goals away from “the percentage place in name-brand colleges” to “ the percentage dedicating themselves to lives of service.”

Social Order (Friendly Corrosion)

Quakerism: a view from the back benches

Copyright 1966 The Back Benches

Social Order (Friendly Corrosion)

The thing which should be said about the concept of a social order is that we are for it - we believe in a system of expectations which ties people together sufficiently well so that they can concentrate on the important things.

But the concept of social order, unfortunately, is generally not the same as the reality. We understand St. Paul’s words to mean that God blesses the idea of ordering human affairs - not that specific orders characterized by slavery, exploitation, and other evils are blessed. Indeed, it seems clear that all societies which ever have existed badly needed changing, and some needed (and need) revolution.

There is a tension, then, between the need for and legitimacy of order (and an authority representing that order), and the need to change that order. Where such a tension exists, we clearly need the guidance of the Light, and a characteristic of Quaker civil disobedience has been this sober leaning on the Light. Indeed, Friends generally obey constitutional authority except when it is clearly invading our rights as children of God, or when we are challenging it for the sake of our brothers.

What this means, of course, is that conflict is built into our relationship to society, and that it is a misplaced emphasis to equate the peace testimony with “harmony.” The excitement generated in Quaker circles by the concept of nonviolence is partly a result of its being a set of techniques which make it possible to work for peace and justice, and to face honestly the creative possibilities in conflict both within and outside the Society of Friends. (See the chapter entitled “Conflict and Controversy” for a fuller exposition of the possibilities which conflict and controversy afford within a Meeting.)

Someone always pays a price for social change. There is no change which does not hurt or inconvenience some in the short run. Yet Friends are among the privileged groups in this country and as unwilling as most to share in paying the price of social change. (“I am moving to the suburbs to get to the better schools - let someone else bear the burden of integrating with the deprived groups.” “If we stay in this changing neighborhood, our house may be broken into. Let someone else take that risk.”) We suggest that the task of discipleship requires that we take on our own privileged shoulders a part of the load from those who are, judging from crime and infant mortality statistics, floundering under its brutal heaviness.

The social order does, of course, involve politics. To help support a Quaker case worker while supporting a government which multiplies (by sins of omission as well as commission) the number of needy cases reveals a pathetic short-sightedness, a lack of political understanding which has long been our weakness. The approaching revolution of cybernation (automatic machines plus computers) may call for a new testimony about the social order based on searching study. It may test whether a dynamic Society of Friends really has what it takes to survive the twentieth century.

Copyright 1966 The Back Benches

Social Order (Friendly Corrosion)

The thing which should be said about the concept of a social order is that we are for it - we believe in a system of expectations which ties people together sufficiently well so that they can concentrate on the important things.

But the concept of social order, unfortunately, is generally not the same as the reality. We understand St. Paul’s words to mean that God blesses the idea of ordering human affairs - not that specific orders characterized by slavery, exploitation, and other evils are blessed. Indeed, it seems clear that all societies which ever have existed badly needed changing, and some needed (and need) revolution.

There is a tension, then, between the need for and legitimacy of order (and an authority representing that order), and the need to change that order. Where such a tension exists, we clearly need the guidance of the Light, and a characteristic of Quaker civil disobedience has been this sober leaning on the Light. Indeed, Friends generally obey constitutional authority except when it is clearly invading our rights as children of God, or when we are challenging it for the sake of our brothers.

What this means, of course, is that conflict is built into our relationship to society, and that it is a misplaced emphasis to equate the peace testimony with “harmony.” The excitement generated in Quaker circles by the concept of nonviolence is partly a result of its being a set of techniques which make it possible to work for peace and justice, and to face honestly the creative possibilities in conflict both within and outside the Society of Friends. (See the chapter entitled “Conflict and Controversy” for a fuller exposition of the possibilities which conflict and controversy afford within a Meeting.)

Someone always pays a price for social change. There is no change which does not hurt or inconvenience some in the short run. Yet Friends are among the privileged groups in this country and as unwilling as most to share in paying the price of social change. (“I am moving to the suburbs to get to the better schools - let someone else bear the burden of integrating with the deprived groups.” “If we stay in this changing neighborhood, our house may be broken into. Let someone else take that risk.”) We suggest that the task of discipleship requires that we take on our own privileged shoulders a part of the load from those who are, judging from crime and infant mortality statistics, floundering under its brutal heaviness.

The social order does, of course, involve politics. To help support a Quaker case worker while supporting a government which multiplies (by sins of omission as well as commission) the number of needy cases reveals a pathetic short-sightedness, a lack of political understanding which has long been our weakness. The approaching revolution of cybernation (automatic machines plus computers) may call for a new testimony about the social order based on searching study. It may test whether a dynamic Society of Friends really has what it takes to survive the twentieth century.

Chapter III THE MEETING FOR WORSHIP

Quakerism: a view from the back benches

Copyright 1966 The Back Benches

Chapter III

Copyright 1966 The Back Benches

Chapter III

THE MEETING FOR WORSHIP

Is Thee Worshiping More and Enjoying it Less?

Is Thee Worshiping More and Enjoying it Less?

We are convinced that the experience of worship is central to our lives as Quakers and to the continued vitality of the Religious Society of Friends. For each, worship should be the whole of life. The “meetings for worship,” those times when Friends gather formally to worship together, should be seen in the context of a larger whole. And Friends should not limit such meetings to 11:00 a.m. on Sundays at a meeting house, but should accept all occasions which arise to worship together.

The meeting for worship is a corporate activity which, at its best, results in a spiritual experience for those attending. We feel a need for a definition in modern terms of the aim of the meeting for worship to speak to current generations. The aim must be common to the worshipping group, but it must be expressed in forms meaningful to the various views of Friends. And we must be cautious of words, for they are crude reflections of the reality we seek.

Friends believe that something will happen when we gather and, expecting or hoping, fall into silence. We recognize the happening when it occurs and the prophetic ministry which sometimes results. But our articulation of explanations of these things which we recognize must be secondary to the experience. We need freedom of expression, but should exercise that freedom with discipline.

Our meetings are “unprogrammed”. However, they should not be formless. We all have tendencies to fall away from the light into mechanical routine, into observance of ritual. When this occurs and form comes from without, we should be willing to make mechanical changes, to carry the pattern of outward action, so that a frozen style of “Sunday morning thinking” is shattered. To centerdown, one should approach worship as a new experience each time.

We recommend a relaxed and informal attitude to the outward trappings. It may be hard to arrive at meeting in tolerance of mind when trying to look too nice or to correct each fault one’s children may display.The ills of meetings for worship are simple to catalog: dead silence, excessive silence which regards outer disturbances as offenses against holiness, obsessive and excessive vocal ministry; debates; long and rambling speeches; entertainments; quotes; clippings; too detailed family history or person anecdotes; purloined “nice ideas”; speakers frequent and swift upon their predecessors.

The cures are almost as easy to articulate: (1) individual preparation for meeting through silence, study and prayer so that one enters meeting “strong and stilled and loving,” (2) education of ourselves and the meeting in the purpose, methods and history of Friends worship so all share a knowledge of the goal, recognize the “ministry of listening” and, if moved to speak, avoid recognized pitfalls of ministry, (3) discipline of self to act on our knowledge of proper methods, to hold distractions and distracters in love, to restrain light, frivolous or bitter reactions to events outside our own silence, and (4) discipline of the group by consensus through appointed Friends who consider, at length and at a distance, the needs of the meeting and all the Friends therein and who are able to guide, admonish and encourage Friends in the best ways to improve the meeting for worship.

We are aware of much concern in the Society about vocal ministry. We suggest that more explicit action be taken to guide would-be ministers. All members might be asked to meet to discuss criteria for speaking in meeting. Brevity, clarity and directness should be encouraged. Constant challenges to accept a point of view or a concern may be directed to a more appropriate place for expression and action. Methods of testing leadings, of quenching and waiting can be taught. It can be stressed that the purpose of the meeting is not psychiatric therapy. Appropriate messages will come more readily when Friends are intent of expressions of truth, rather than of ourselves, on expression worthy of the presence we invoke, rather than of the world around us. The leading to speak should cause a personal crisis; the proper response, a sense of comfort. Let us beware of overreaching and of resignation. Let us be aware that the meeting for worship is not our own personal affair.

We suggest that Friends consider the times of the meetings. It may be that mid-week meetings for worship will strengthen the meeting. A period prior to meetings for worship when Friends gather in silence and reverence to do useful manual work may be better preparation than discussion groups or intellectual study. Discussion and intellectual stimulation seem more appropriate after worship. Appointed periods of silence in which all Friends are asked to consider a prearranged subject are a useful supplement to the usual worship. To fit such programs in to the usual time, it might be scheduled: 9:00 a.m. - 1o:00 a.m. group preparation for worship; 10:00 a.m. - 11:00 a.m., Meeting for Worship, 11:00 a.m - 12:00 noon, discussion or programmed meeting. Such changes might help us to utilize more efficiently our resources. We also suggest adopting a general policy not to break the meeting for worship until at least ten minutes after the last message has been delivered.

It is evident to us that improvement in our meetings for worship is indissolubly linked to solution of the other problems currently confronting the Society of Friends; each Sunday morning meeting for worship will influence and will reflect our attitudes towards and actions in the other areas discussed in this paper.

We worship together because the sum is greater than the parts, because the confluence of many experiences is one experience for all, because worship is work and many together working to one end make the task easier for each, and because the example and advice of others at our side help to dampen our excesses and raise our sometime depressions. When we truly worship together we grow to love one another and as we love, we are drawn into deeper communion.

We feel that the goal is worth the cost of gaining it.

CHAPTER IV QUAKER ORGANIZATION:

Quakerism: a view from the back benches

Copyright 1966 The Back Benches

CHAPTER IV

Copyright 1966 The Back Benches

CHAPTER IV

QUAKER ORGANIZATION:

A Side Long Glance

A Side Long Glance

Are the units of organization in the Religious Society of Friends productive? Are the efficient? Can the unites “at work” produce maximum gain? If there are limitations, what are they?

There have been changes in structure over the centuries, or changes in emphases and role, surely… each change answering new needs. In terms of today’s needs, are there appropriate criticisms of our Society’s organisms and suitable alternatives available for consideration?

If the technical organization exists to serve the spiritual purposes of the Society, perhaps we have moved quite unintentionally into a situation where we are serving the institutions of the Society, possibly beyond their capacity to be useful.

To review our current organizational posture, we see that the Monthly Meeting is the local unit, the congregation. The Monthly Meeting, or in some cases the Preparative Meeting, embodying procedures for worship and action, is the unit to which the individual Friend relates. The local Meeting tends to be the most sensitive instrument, for basic confrontation of individuals occurs here. One “lives” with the local Meeting. Understanding, accommodation and growth therefore can occur most substantially in a local Meeting.

Beyond the local Meeting are the Quarterly Meeting and the Yearly Meeting. (There are other variations throughout the United States, I.e., regional associations). These conduct some common endeavors when needed and provide limited opportunities for sharing, consultation and fellowship.

Beyond the Yearly Meeting level, Friends meet at the consultative level. Friends World Committee are examples: what occurs is not by authority but by common consent. With responsibility for husbandry of Quaker values and certain prescribed activities, these unites tend to function not as advanced leadership but as the least common denominator of administration.

Internal critics of Quakerism are torn between the poles of authoritative action and decisiveness and the equally important virtues of decentralization. Can a life be found for Quakerism which will permit action yet leave the Society free of higher-than-thou authorities?

No doubt, some of the suggestions which follow may seem to duplicate those in the chapter on Community. They are really the same concern looked at from a different angle.

Does a Meeting Exist to Maintain Property?

Quakerism: a view from the back benches

Copyright 1966 The Back Benches

Does a Meeting Exist to Maintain Property?

Only a rare Monthly Meeting devotes its time and energy and money for service outside the Society. When questions of activity in the community arise, the few individuals pressing for decision are often discouraged or, worse, referred to committee. The constant concern for meeting house maintenance, property needs, cemetery upkeep, or new building funds, suggests an inner weakness of the Society. An illusion of activity and importance is created by these building and property concerns, but in terms of the higher calling of the Quakers, this is no activity at all worthy of the name of Quaker. Any fair time-study of the average meeting for business would undoubtedly reveal an undue proportion of time and money given to housekeeping functions. It is no wonder few people attend meetings for business.

The question arises: is there a possibility Quakers should give up these cumbersome properties? Why are they so sacred? Why is any particular meeting house of concern to Quakers, as Quakers? If an historical society is interested, perhaps it could maintain such a place as a museum.

All cemeteries should be turned over to a Friend Cemetery Corporation or corporations formed exclusively for this purpose.

Is there a meeting house that is used through the week, that is really a community center? Given Quaker insights, most meeting houses should be closed and no new ones should be built until we can justify their possession not only by the ease with which we can handle their maintenance, but also by the service to which we put them. To obtain maximum utility, we might cooperate with other groups in building facilities. The Quaker test, seldom expressed this way, is really utility, usefulness to the Lord.

A hard Quaker look at facilities would refresh the entire religious community, itself overloaded with property and buildings for its churches. And Friends should re-evaluate our acceptance of the special privilege of tax-exempt status for religious organizations. A fresh Quaker response on this question would prompt the comment, “just what you would expect of Quakers.”

Copyright 1966 The Back Benches

Does a Meeting Exist to Maintain Property?